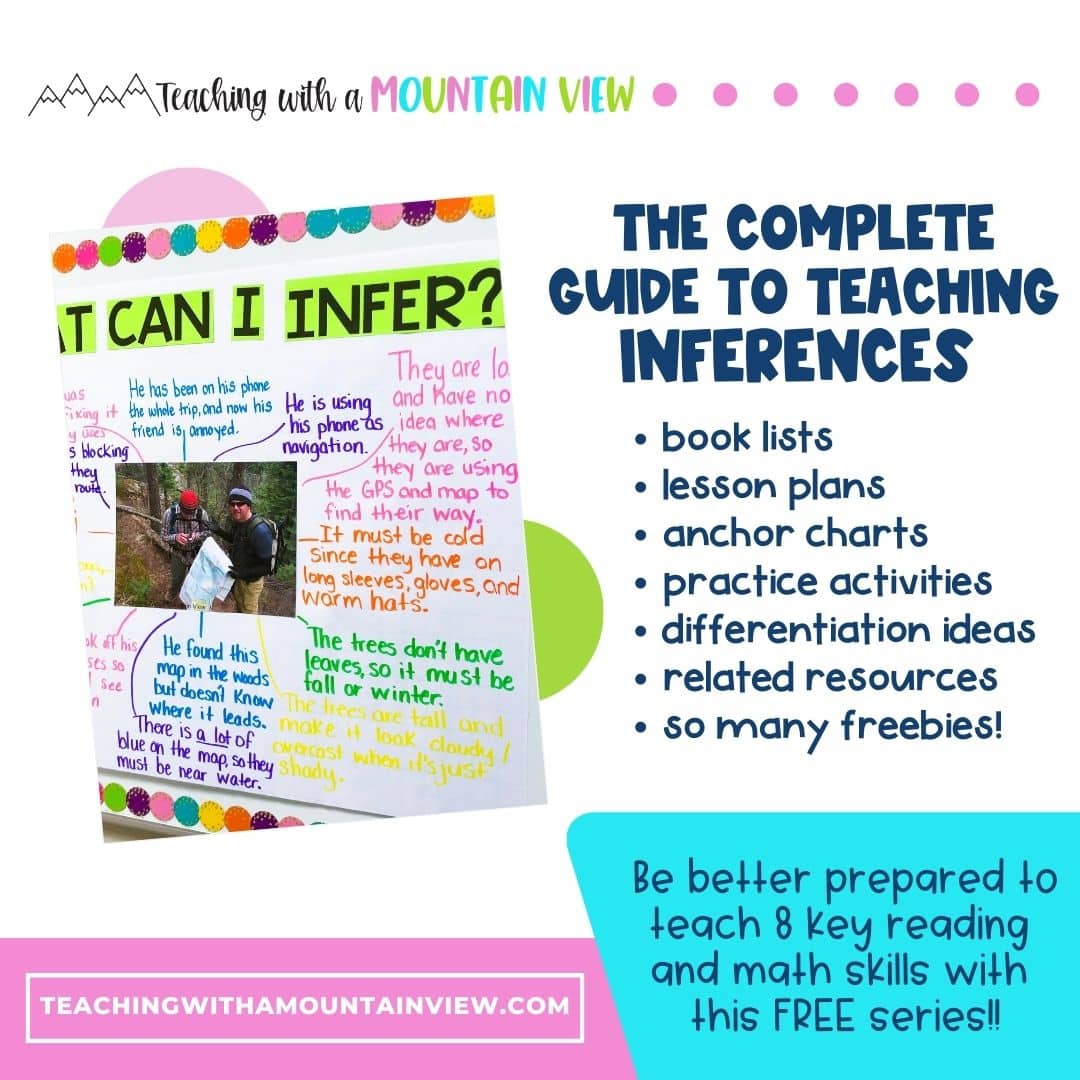

Skilled reading requires students to become adept with many different cognitive processes. Being able to make inferences sets students up for success in reading comprehension. One of the best ways to develop automaticity with inference (being able to make inferences automatically) is explicitly teaching inference and providing numerous opportunities to practice.

This free PDF guide will allow you to have all of the inference resources right at your fingertips. It’s packed with checklists, book lists, lesson plans, anchor charts, practice activities, and more!

It’s important for most upper elementary students to understand the difference between inferences and predictions. This can be very difficult for students to understand though, so make a determination about the appropriateness of teaching the difference between these two in your classroom.

Prediction: What do you think will happen in the future based on what you know so far? Make a guess based on what you know. A prediction is often proven wrong or right after you continue reading.

Inference: What can you infer about what’s happening right now based on what you read/saw and what you already know? An inference may never be completely explained or verified.

Text Evidence + Schema/Background Knowledge = Inference

I teach inferencing with a scaffolded approach, rotating between using pictures and texts to practice the skills. I also teach inference lessons after teaching or reviewing key details and text evidence, since both become an important part of making inferences. This is our usual progression:

More information is included in your FREE teaching inference PDF above, but here are a few highlights.

We watch the short, animated video “Snack Attack” on YouTube. I stop at specific moments to ask questions about the video. I don’t necessarily use the terms “inference” here. I just ask them questions, which they view more as making a prediction at this point.

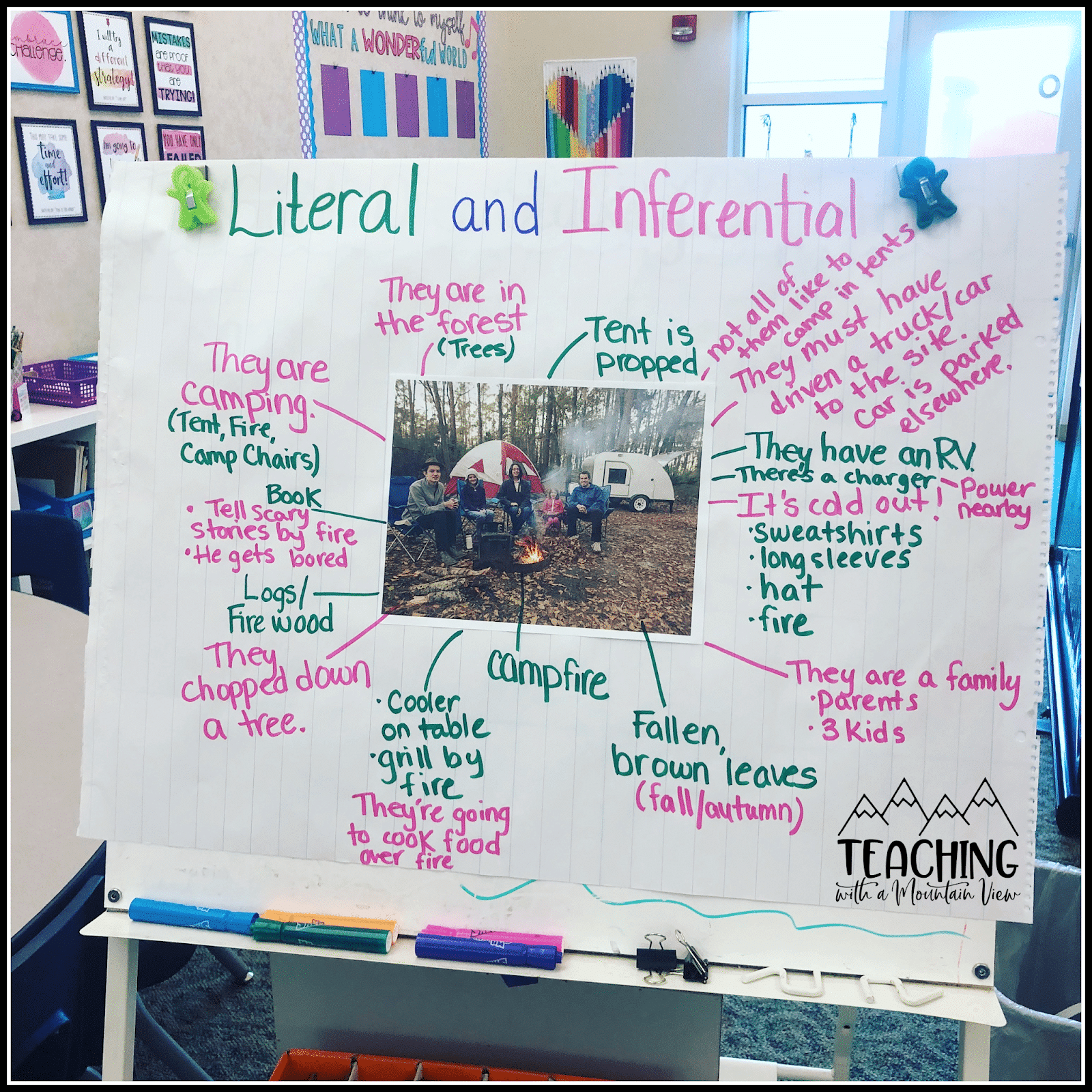

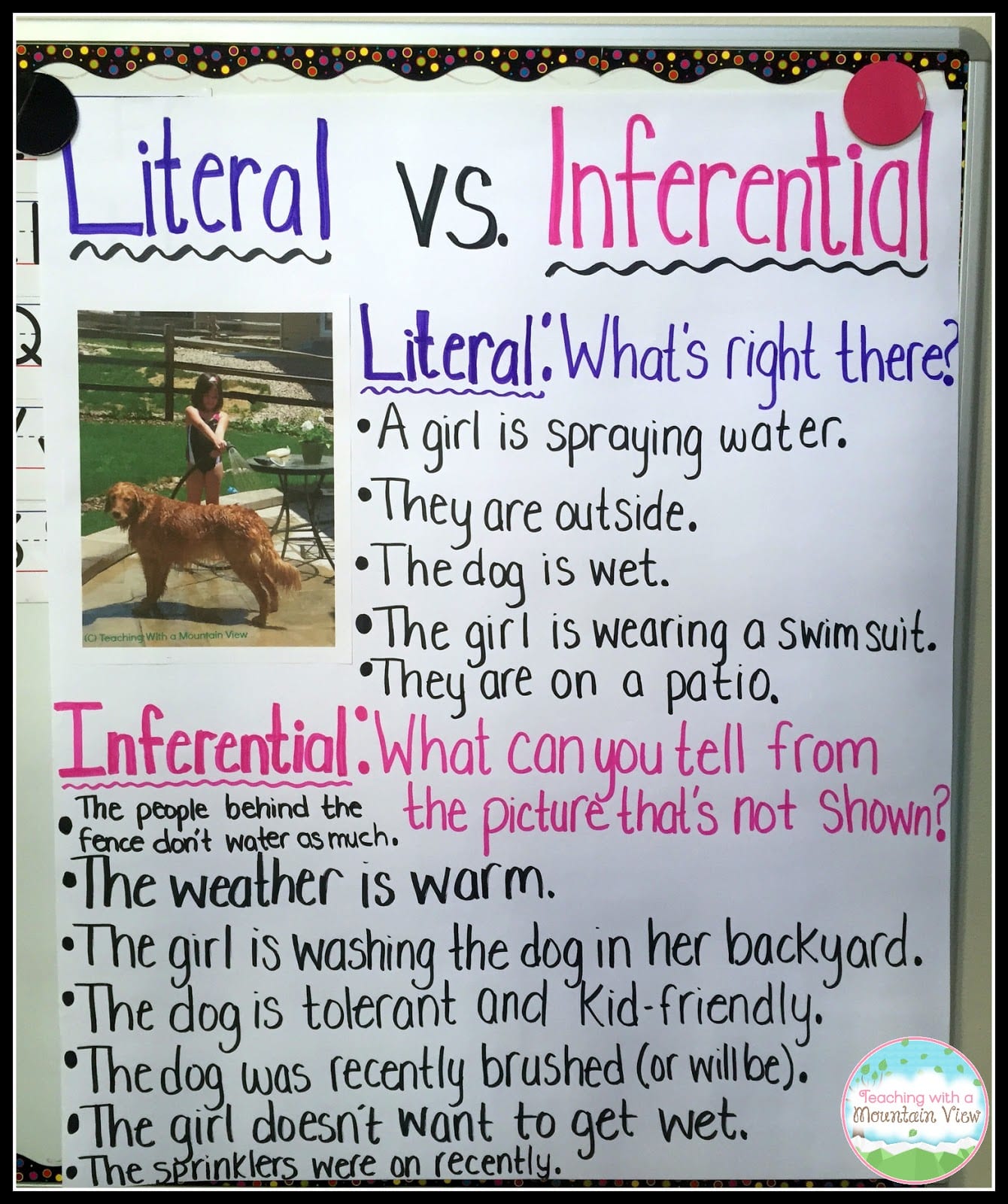

After the video introduction, I show my students a picture. I ask them to tell me everything they notice about the picture. I write down everything they mention around the picture, and they will almost always include inferences without realizing it. Silently – without pointing out the difference – I color-code their statements using one color for inferences and one color for observations. After we’ve surrounded the photo with observations and inferences, I ask them if they can figure out the reason why I used two different colors. I ask them to look at the differences between the statements. It’s at this point that they usually come up with their own definitions of observations vs. inference. If they don’t, I guide them to it.

We complete a similar activity again, but this time we use our observations to make inferences, a critical prerequisite skill to making inferences in texts. I have the pictures and pages for this lesson all ready for you to teach this portion of the lesson in your free PDF!

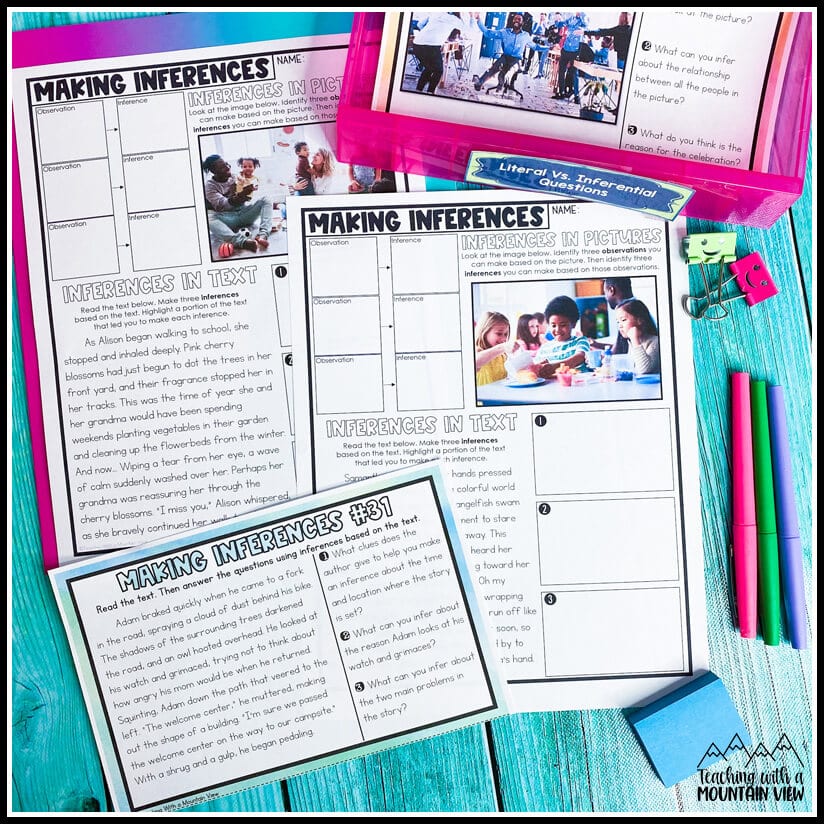

After we have had plenty of practice with making inferences based on observations, we start to transition to making inferences in texts. We do exactly the same procedure as we did with pictures. I pull a line or paragraph out of text and ask them to make as many inferences as they can based on that section. Then, I have students complete tasks that incorporate both pictures and text, highlighting sections of the text to support their inferences.

At this point, I introduce students to the idea of literal vs. inferential questions as they pertain to both text and images. I start back at square one by asking them very literal questions about pictures. Then, I ask them inferential questions. This part is usually quite easy for students at this point since they’ve had so much practice. Then, I do the same with texts – asking both literal and inferential questions.

This is an optional lesson. I like to use the shark scene from Finding Nemo. It’s a great opportunity for students to use their background knowledge about fish and sharks along with what is happening in the scene to make inferences. They can infer that the shark is luring the fish in to eat them. They can infer that the fish know sharks are not to be trusted. They can make inferences about the small whiff of blood the shark gets that requires an “intervention.” They can also make a prediction (that the fish are going to be eaten or the shark wants to eat them) that will later be proven right or wrong. This is a great time to talk about plot twists as well!

Your free PDF guide has several more ideas for practicing inferences, but here are a few favorites.

Mystery Bags: This is a twist on the typical “all about me bag.” My kids LOVE this, and I love incorporating it into morning meeting at the beginning of the year! I have each student anonymously bring in a bag filled with items that describe them. It can be sports medals, paint brushes, a rock collection, etc. I pull out each item, and we make as many inferences and observations as we can about the contents and the owner. Then, the owner of the bag comes up and explains each item, and we talk about the inferences that were made. This pairs perfectly with Milo Imagines the World (Amazon affiliate link).

Reader’s Theatre: Building fluency skills are critical, and I love to incorporate reading skills into fluency practice as much as possible (Remember the importance of inference becoming automatic? That’s a huge part of this!) I created these Reader’s Theatre sets specifically to practice fluency. I also included one free set at the end of the PDF to get you started!

First Page Ponderings: I copy the first page of many different books. I hang them up around the room with some guiding inference questions (or if you are teaching 5th grade+ you may not need these guiding questions) and have students make a ton of inferences based on the first page of the book. This is amazing because it gives students previews of many books! We follow up the activity by selecting one or two of the books and following up on the questions. You can visit this post to learn more about it!

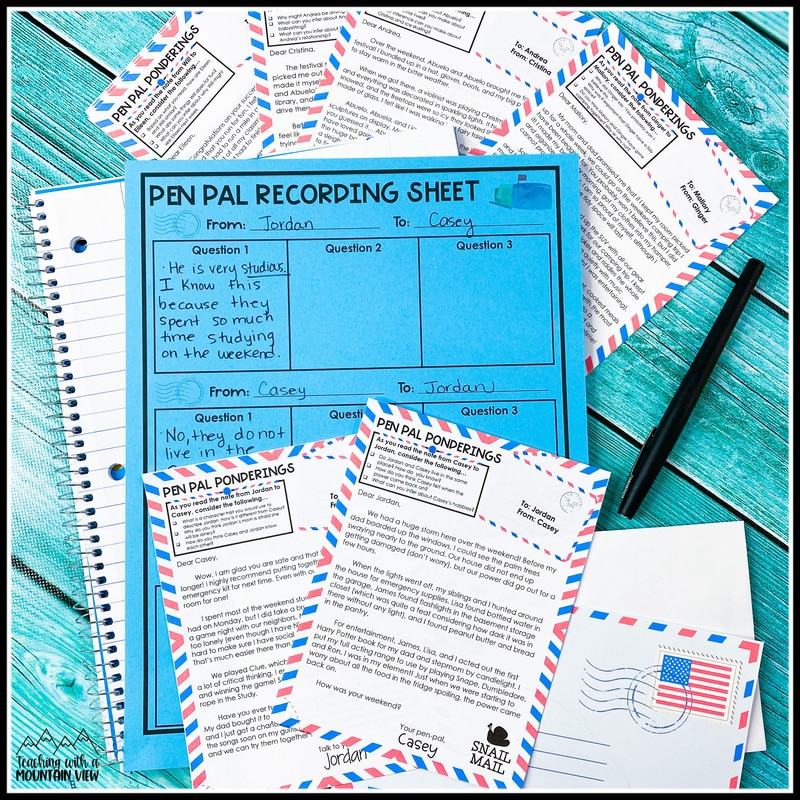

Pen Pal Letters: You can either use premade letters for students to make inferences from or have students write their own letters, which they love. Ask your students to pretend they are writing a letter to a new pen pal. I tell them to ask several questions and give plenty of information about where they live, what they like, etc. If you want to increase the rigor and incorporate social studies or geography, have another student respond to the letter while imagining they are a child from a specific region or location.